Contents

This technical overview goes into greater detail about the implementation of ROS. Most ROS users do not need to know these details, but they are important for those wishing to write their own ROS client libraries or those wishing to integrate other systems with ROS.

This technical overview assumes that you are already familiar with the ROS system and its concepts. For example, the ROS conceptual overview provides an overview of the Computation Graph architecture, including the role of the ROS Master and nodes.

Master

The Master is implemented via XMLRPC, which is a stateless, HTTP-based protocol. XMLRPC was chosen primarily because it is relatively lightweight, does not require a stateful connection, and has wide availability in a variety of programming languages. For example, in Python, you can start any Python interpreter and begin interacting with the ROS Master:

$ python

>>> from xmlrpclib import ServerProxy

>>> import os

>>> master = ServerProxy(os.environ['ROS_MASTER_URI'])

>>> master.getSystemState('/')

[1, 'current system state', [[['/rosout_agg', ['/rosout']]], [['/time', ['/rosout']], ['/rosout', ['/rosout']], ['/clock', ['/rosout']]], [['/rosout/set_logger_level', ['/rosout']], ['/rosout/get_loggers', ['/rosout']]]]]The Master has registration APIs, which allow nodes to register as publishers, subscribers, and service providers. The Master has a URI and is stored in the ROS_MASTER_URI environment variable. This URI corresponds to the host:port of the XML-RPC server it is running. By default, the Master will bind to port 11311.

For more information, including an API listing, please see Master API.

Parameter Server

Although the Parameter Server is actually part of the ROS Master, we discuss its API as a separate entity to enable separation in the future.

Like the Master API, the Parameter Server API is also implemented via XMLRPC. The use of XMLRPC enables easy integration with the ROS client libraries and also provides greater type flexibility when storing and retrieving data. The Parameter Server can store basic XML-RPC scalars (32-bit integers, booleans, strings, doubles, iso8601 dates), lists, and base64-encoded binary data. The Parameter Server can also store dictionaries (i.e. structs), but these have a special meaning.

The Parameter Server uses a dictionary-of-dictionary representation for namespaces, where each dictionary represents a level in the naming hierarchy. This means that each key in a dictionary represents a namespace. If a value is a dictionary, the Parameter Server assumes that it is storing the values of a namespace. For example, if you were to set the parameter /ns1/ns2/foo to the value 1, the value of /ns1/ns2/ would be a dictionary {foo : 1} and the value of /ns1/ would be a dictionary {ns2 : { foo : 1 }}.

The XMLRPC API makes it very easy to integrate Parameter Server calls without even having to use a ROS client library. Assuming you have access to an XMLRPC client library, you can make calls directly. For example:

$ python

>>> from xmlrpclib import ServerProxy

>>> import os

>>> ps = ServerProxy(os.environ['ROS_MASTER_URI'])

>>> ps.getParam('/', '/foo')

[-1, 'Parameter [/bar] is not set', 0]

>>> ps.setParam('/', '/foo', 'value')

[1, 'parameter /foo set', 0]

>>> ps.getParam('/', '/foo')

[1, 'Parameter [/foo]', 'value']Please see Parameter Server API for a detailed API listing.

Node

A ROS node has several APIs:

A slave API. The slave API is an XMLRPC API that has two roles: receiving callbacks from the Master, and negotiating connections with other nodes. For a detailed API listing, please see Slave API.

A topic transport protocol implementation (see TCPROS and UDPROS). Nodes establish topic connections with each other using an agreed protocol. The most general protocol is TCPROS, which uses persistent, stateful TCP/IP socket connections.

A command-line API. Every node should support command-line remapping arguments, which enable names within a node to be configured at runtime.

Every node has a URI, which corresponds to the host:port of the XMLRPC server it is running. The XMLRPC server is not used to transport topic or service data: instead, it is used to negotiate connections with other nodes and also communicate with the Master. This server is created and managed within the ROS client library, but is generally not visible to the client library user. The XMLRPC server may be bound to any port on the host where the node is running.

The XMLRPC server provides a Slave API, which enables the node to receive publisher update calls from the Master. These publisher updates contain a topic name and a list of URIs for nodes that publish that topic. The XMLRPC server will also receive calls from subscribers that are looking to request topic connections. In general, when a node receives a publisher update, it will connect to any new publishers.

Topic transports are negotiated when a subscriber requests a topic connection using the publisher's XMLRPC server. The subscriber sends the publisher a list of supported protocols. The publisher then selects a protocol from that list, such as TCPROS, and returns the necessary settings for that protocol (e.g. an IP address and port of a TCP/IP server socket). The subscriber then establishes a separate connection using the provided settings.

Topic Transports

There are many ways to ship data around a network, and each has advantages and disadvantages, depending largely on the application. TCP is widely used because it provides a simple, reliable communication stream. TCP packets always arrive in order, and lost packets are resent until they arrive. While great for wired Ethernet networks, these features become bugs when the underlying network is a lossy WiFi or cell modem connection. In this situation, UDP is more appropriate. When multiple subscribers are grouped on a single subnet, it may be most efficient for the publisher to communicate with all of them simultaneously via UDP broadcast.

For these reasons, ROS does not commit to a single transport. Given a publisher URI, a subscribing node negotiates a connection, using the appropriate transport, with that publisher, via XMLRPC. The result of the negotiation is that the two nodes are connected, with messages streaming from publisher to subscriber.

Each transport has its own protocol for how the message data is exchanged. For example, using TCP, the negotiation would involve the publisher giving the subscriber the IP address and port on which to call connect. The subscriber then creates a TCP/IP socket to the specified address and port. The nodes exchange a Connection Header that includes information like the MD5 sum of the message type and the name of the topic, and then the publisher begins sending serialized message data directly over the socket.

To emphasize, nodes communicate directly with each other, over an appropriate transport mechanism. Data does not route through the master. Data is not sent via XMLRPC. The XMLRPC system is used only to negotiate connections for data.

Developer links:

Message serialization and msg MD5 sums

Messages are serialized in a very compact representation that roughly corresponds to a c-struct-like serialization of the message data in little endian format. The compact representation means that two nodes communicating must agree on the layout of the message data.

Message types (msgs) in ROS are versioned using a special MD5 sum calculation of the msg text. In general, client libraries do not implement this MD5 sum calculation directly, instead storing this MD5 sum in auto-generated message source code using the output of roslib/scripts/gendeps. For reference, this MD5 sum is calculated from the MD5 text of the .msg file, where the MD5 text is the .msg text with:

- comments removed

- whitespace removed

- package names of dependencies removed

- constants reordered ahead of other declarations

In order to catch changes that occur in embedded message types, the MD5 text is concatenated with the MD5 text of each of the embedded types, in the order that they appear.

Establishing a topic connection

Putting it all together, the sequence by which two nodes begin exchanging messages is:

- Subscriber starts. It reads its command-line remapping arguments to resolve which topic name it will use. (Remapping Arguments)

- Publisher starts. It reads its command-line remapping arguments to resolve which topic name it will use. (Remapping Arguments)

- Subscriber registers with the Master. (XMLRPC)

- Publisher registers with the Master. (XMLRPC)

- Master informs Subscriber of new Publisher. (XMLRPC)

- Subscriber contacts Publisher to request a topic connection and negotiate the transport protocol. (XMLRPC)

- Publisher sends Subscriber the settings for the selected transport protocol. (XMLRPC)

- Subscriber connects to Publisher using the selected transport protocol. (TCPROS, etc...)

The XMLRPC portion of this will look like:

/subscriber_node → master.registerSubscriber(/subscriber_node, /example_topic, std_msgs/String, http://hostname:1234)

- Master returns that there are no active publishers.

/publisher_node → master.registerPublisher(/publisher_node, /example_topic, std_msgs/String, http://hostname:5678)

Master notices that /subscriber_node is interested in /example_topic, so it makes a callback to the subscriber

master → subscriber.publisherUpdate(/publisher_node, /example_topic, [http://hostname:5678])

Subscriber notices that it has not connected to http://hostname:5678 yet, so it contacts it to request a topic.

subscriber → publisher.requestTopic(/subscriber_node, /example_topic, [[TCPROS]])

Publisher returns TCPROS as the selected protocol, so subscriber creates a new connection to the publishers TCPROS host:port.

Example

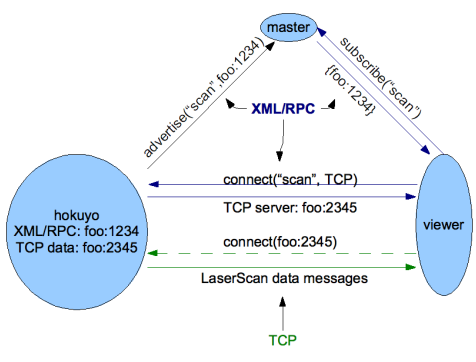

To control a Hokuyo laser range-finder, we start the hokuyo_node node, which talks to the laser and publishes sensor_msgs/LaserScan messages on the scan topic. To visualize the laser scan data, we start the rviz node and subscribe to the scan topic. After subscription, the rviz node begins receiving LaserScan messages, which it renders to the screen.

Note how the two sides are decoupled. All the hokuyo_node node does is publish scans, without knowledge of whether anyone is subscribed. All the rviz does is subscribe to scans, without knowledge of whether anyone is publishing them. The two nodes can be started, killed, and restarted, in any order, without inducing any error conditions.

In the example above, how do the laser_viewer and hokuyo_node nodes find each other? They use a name service that is provided by a special node called the master. The Master has a well-known XMLRPC URI that is accessible to all nodes. Before publishing on a topic for the first time, a node advertises its intent to publish on that topic. This advertisement sends to the master, via XMLRPC, information about the publication, including the message type, the topic name, and the publishing node's URI. The master maintains this information in a publisher table.

When a node subscribes to a topic, it communicates with the master, via XMLRPC, sending the same information (message type, topic name, and node URI). The master maintains this information in a subscriber table. In return, the subscriber is given the current list of publisher URIs. The subscriber will also receive updates from the master as the list of publishers changes. Given the list of publishers, the subscribing node is ready to initiate transport-specific connections.

Note: message data does not flow through the master. It only provides name service, connecting subscribers with publishers.

Establishing a service connection

We have not discussed services as much in this overview, but they can be viewed as a simplified version of topics. Whereas topics can have many publishers, there can only be a single service provider. The most recent node to register with the master is considered the current service provider. This allows for a much simpler setup protocol -- in fact, a service client does not have to be a ROS node.

- Service registers with Master

- Service client looks up service on the Master

- Service client creates TCP/IP to the service

Service client and service exchange a Connection Header

- Service client sends serialized request message

- Service replies with serialized response message.

If the last several steps look familiar, its because they are an extension of the TCPROS protocol. In fact, rospy and roscpp both use the same TCP/IP server socket to receive both topic and service connections.

As there is no callback from the Master when a new service is registered, many client libraries provide a "wait for service" API method, that simply polls the Master until a service registration appears.

Persistent service connections

By default, service connections are stateless. For each call a client wishes to make, it repeats the steps of looking up the service on the Master and exchanging request/response data over a new connection.

The stateless approach is generally more robust as it allows a service node to be restarted, but this overhead can be high if frequent, repeated calls are made to the same service.

ROS allows for persistent connections to a service, which provide a very high-throughput connection for making repeated calls to a service. With these persistent connections, the connection between the client and service is kept open so that the service client can continue to send requests over the connection.

Greater care should be used with persistent connections. If a new service provider appears, it does not interrupt an ongoing connection. Similarly, if a persistent connection fails, there is no attempt made to reconnect.